INTRODUCTION

Eight of the eleven articles in the most recent issue of the Harvard Theological Review discuss the authenticity of the so-called Gospel of Jesus Wife (GJW), which Karen King publicized through a shrewdly-orchestrated media frenzy in September 2012. The core relevant articles include a survey of the papyrus scrap by King, a refutation of authenticity by Leo Depuydt and a response by King. Five supporting articles detail two spectroscopy examinations of the ink (Yardley and Hagadorn; Azzarelli, Goods, Swager), two radiocarbon datings of the papyrus (Hodgins; Tuross), and a paleographic evaluation (Choat).

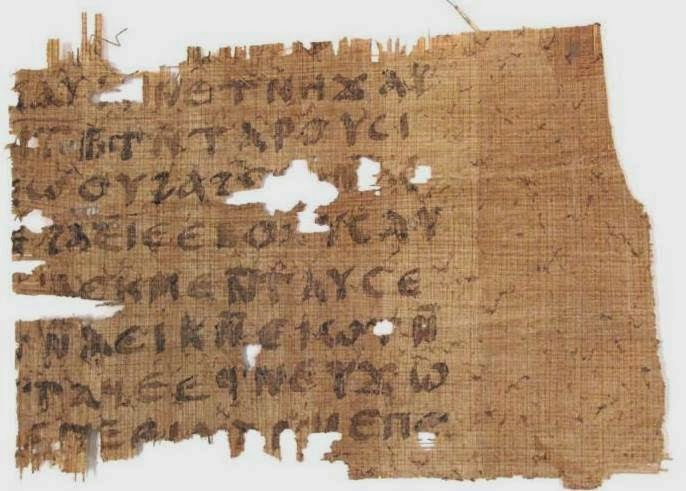

Karen King´s initial argument that this fragment demonstrates a fourth century literary manuscript of the “the Gospel of Jesus Wife” is now officially dead, by her own admission. We are left with a deflated seventh to ninth century semi-literary scrap ... or a fraud. We have no plausible direct literary evidence for a new non-canonical gospel. The question remains as to whether we should recognize this scrap as an ancient semi-literary document or a modern fraud. According to King, the arguments concerning fraud are highly problematic, and the scientific and linguistic evidence repeatedly affirm authenticity.

According to the results, the ink used is indeed the most obvious choice for a modern forger — carbon ink. The ink is composed of soot. “The inks used in this manuscript are primarily based on carbon black pigments such as ‘lamp black.’” (Yardley etal., 164) King attempts to paint the resultant test as proving the implausibility of fraud, arguing that “their research to date shows that details of the Raman spectra of carbon-based pigments in GJW match closely those of several manuscripts from the Columbia collection of papyri dated between 1 B.C.E. and 800 C.E., while they deviate significantly from modern commercial lamp black pigments.” (King, “Jesus said,” 2014, 135) However, no one would suggest that this was forged with modern commercial pigments. Someone would have mixed soot with a solvent, producing the obviously low quality and uneven writing medium on the papyrus.

RADIOCARBON DATING

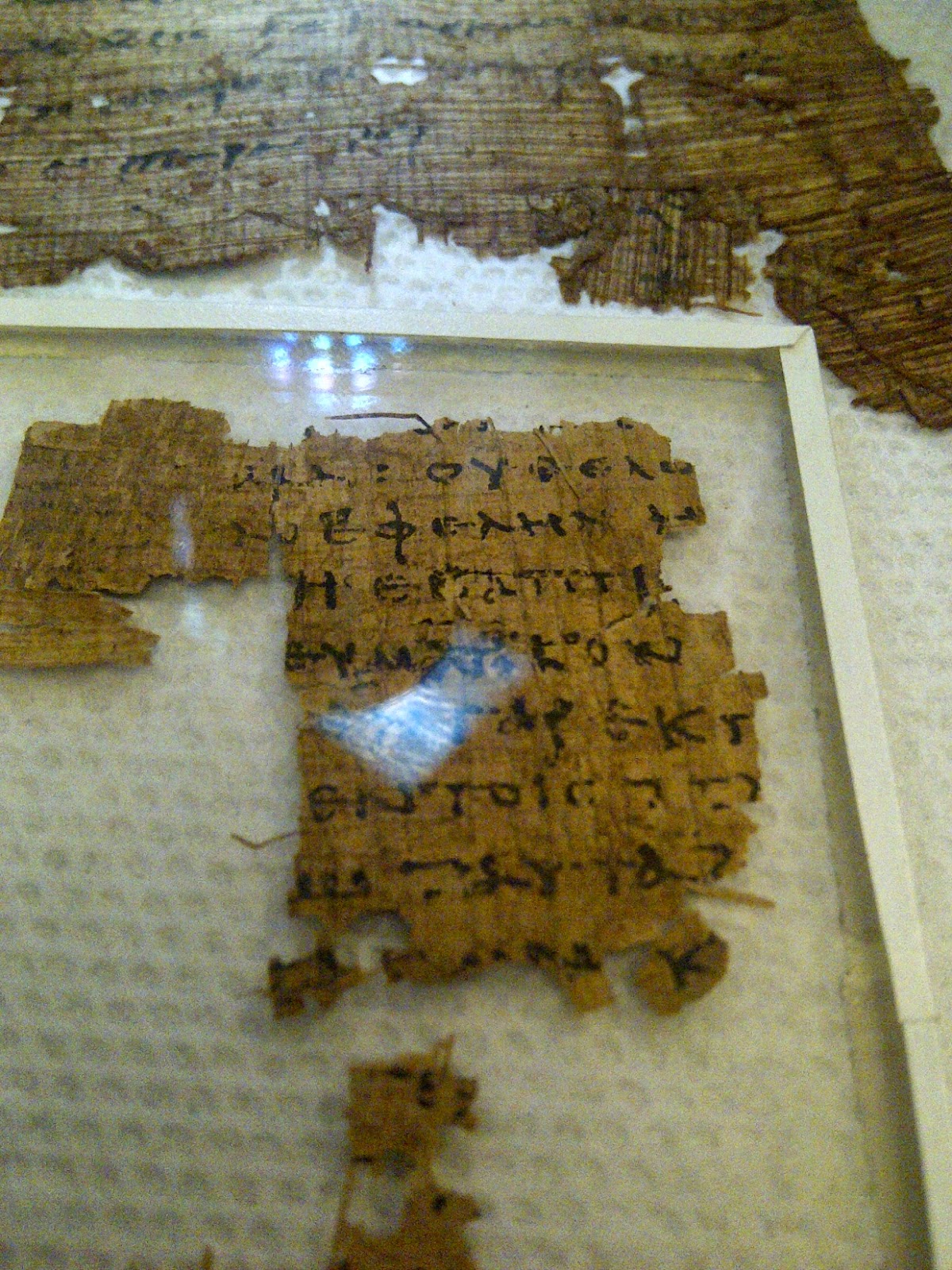

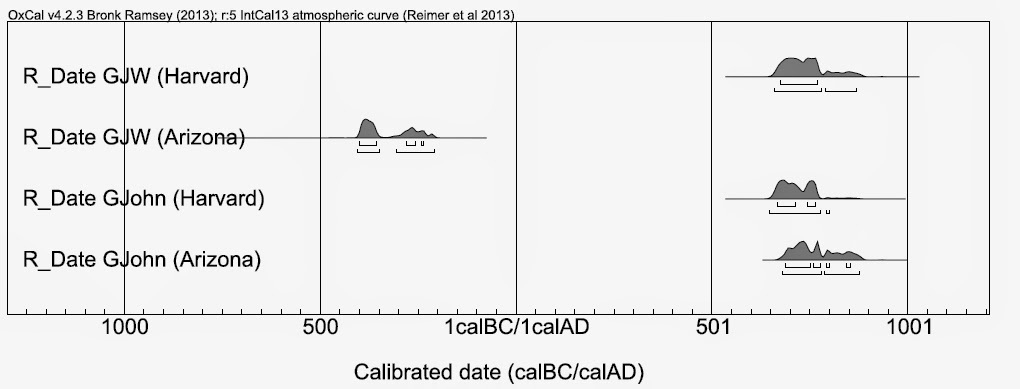

Using two labs, the GJW fragment and a Sahidic John fragment associated with the same papyri lot were carbon dated. The rounded 2-sigma ranges for the manuscripts are as follows:

Only the Harvard report indicates the date of the test (14 March 2014); one might surmise that the second test was ordered after the extremely early date arrived from Arizona. Whatever the case, if one of the two GJW 14C dates were to be accurate, it would probably be the Harvard range (650–870 CE), which is corroborated by the related GJohn manuscript (chart above). Having said this, the result remains somewhat inconclusive. (δ13C levels were also higher than expected, suggesting contamination in all samples.)

So does this confirm the authenticity of the GJW? Such a late dating bulldozes King’s first appraisal of the manuscript as a fourth century witness. The GJW fragment under question is broken on all sides except the top, where apparently the modern forger cut the empty section off of a larger fragment which was in fact ancient. Carbon dating has no value for authenticating such a manuscript, although if the Ptolemaic date (410–200 BCE) offered by the Arizona AMS lab were accurate (of which I am not convinced), fraud would be certain.

PALEOGRAPHY

Choat’s assessment of the scribal hand is hardly an enthusiastic endorsement of its authenticity:

DEPUYDT

Leo Depuydt presents the argument which is accepted by most specialists who are familiar with the GJW. The modern forger (1) created the text by rearranging several sentences from the Gospel of Thomas and (2) unintentionally left evidence of the fraud through two grammatical infelicities ("blunders"). The first is the omission of the object marker ⲙ- in line one (ⲧⲁⲙⲁⲁⲩ ⲁⲥϯ ⲛⲁⲉⲓ ⲡⲱ̣[ⲛϩ]). The second is the awkward construction ⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ (more correctly ⲡⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ or ⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉϥⲑⲟⲟⲩ). Depuydt also mentioned a third serious error, which I believe to be the most damning evidence against authenticity (186); in line 6, the forger has combined a positive habitual from GThomas with a negative habitual to create the nonsense chimera verbal phrase ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ ϣⲁϥⲉ{ⲓ}ⲛⲉ (“Evil man habitually does not he does habitually bring” sic). Notably, Francis Watson, Alin Suciu-Hugo Lundhaug, and Andrew Bernhard have popularized many of these arguments, detailing how Depuydt’s first "blunder" seems to derive from a typo in Michael Grondin’s 2002 online PDF of the Gospel of Thomas.

KING’S RESPONSE ARTICLE

In Karen King’s mind, if one can not exhaustively prove the inauthenticity of the GJW fragment, then it must be accepted as authentic. The results from spectography, radiometric dating and Choat’s paleographic analysis all leave the door open, therefore the fragment is undeniably authentic. Karen King maintains the problematic infinitive form ϣⲁϥⲉ “swell,” and ignores the persuasive reasoning behind the reconstruction of the damning error above. I encountered no serious discussion of this in her original article. In my opinion, this argument alone inauthenticates the GJW fragment, yet King is unconcerned, instead positing an unattested verbal form. I could imagine why someone might differ with me on various issues here, I can not identify with the stiff-necked concluding statement of King: “In conclusion, Depuydt’s essay does not offer any substantial evidence or persuasive argument, let alone unequivocal surety, that the GJW fragment is a modern fabrication (forgery).”

CONCLUSION

If a husband were to genetically test his children to determine whether his wife had been faithful, and the tests returned indicating that the children could not conclusively be proven to not be his, would this assure him of his wife’s fidelity? Could he then, based upon these tests, be confident that he had indeed fathered the children? Karen King has produced no new evidence to authenticate this fragment. On the contrary, her prior contentions that the GJW fragment was (1) part of a literary codex and (2) was fourth century are now indefensible. Her method of argumentation was not self-critical or objective, but will doubtlessly be sufficient for those who already want to believe.

THE HANDWRITTEN NOTE

One has to ask why Karen King has not published the notorious handwritten note. A typed 1982 note signed by Peter Munro accompanied the fragments which indicated that a Coptic John fragment was among the manuscript group (cf. King, “Jesus said,” 2012, 2). The second notorious handwritten note reads as follows:

Larry Hurtado's Announcement

Harvard Gospel of Jesus' Wife website

Harvard Theological Review Issue

Antinoou Coptic font to view Coptic text on this page

Francis Watson maintains inauthenticity (via NT Blog)

Eight of the eleven articles in the most recent issue of the Harvard Theological Review discuss the authenticity of the so-called Gospel of Jesus Wife (GJW), which Karen King publicized through a shrewdly-orchestrated media frenzy in September 2012. The core relevant articles include a survey of the papyrus scrap by King, a refutation of authenticity by Leo Depuydt and a response by King. Five supporting articles detail two spectroscopy examinations of the ink (Yardley and Hagadorn; Azzarelli, Goods, Swager), two radiocarbon datings of the papyrus (Hodgins; Tuross), and a paleographic evaluation (Choat).

Karen King´s initial argument that this fragment demonstrates a fourth century literary manuscript of the “the Gospel of Jesus Wife” is now officially dead, by her own admission. We are left with a deflated seventh to ninth century semi-literary scrap ... or a fraud. We have no plausible direct literary evidence for a new non-canonical gospel. The question remains as to whether we should recognize this scrap as an ancient semi-literary document or a modern fraud. According to King, the arguments concerning fraud are highly problematic, and the scientific and linguistic evidence repeatedly affirm authenticity.

“The scientific testing completed thus far consistently provides positive evidence of the antiquity of the papyrus and ink, including radiocarbon, spectroscopic, and oxidation characteristics, with no evidence of modern fabrication.” (King, “Jesus said,” 2014, 154)THE INK

According to the results, the ink used is indeed the most obvious choice for a modern forger — carbon ink. The ink is composed of soot. “The inks used in this manuscript are primarily based on carbon black pigments such as ‘lamp black.’” (Yardley etal., 164) King attempts to paint the resultant test as proving the implausibility of fraud, arguing that “their research to date shows that details of the Raman spectra of carbon-based pigments in GJW match closely those of several manuscripts from the Columbia collection of papyri dated between 1 B.C.E. and 800 C.E., while they deviate significantly from modern commercial lamp black pigments.” (King, “Jesus said,” 2014, 135) However, no one would suggest that this was forged with modern commercial pigments. Someone would have mixed soot with a solvent, producing the obviously low quality and uneven writing medium on the papyrus.

RADIOCARBON DATING

Using two labs, the GJW fragment and a Sahidic John fragment associated with the same papyri lot were carbon dated. The rounded 2-sigma ranges for the manuscripts are as follows:

GJohn | GJW | |

Harvard | 640–800 CE | 650–870 CE |

Arizona | 680–880 CE | 410–200 BCE |

Only the Harvard report indicates the date of the test (14 March 2014); one might surmise that the second test was ordered after the extremely early date arrived from Arizona. Whatever the case, if one of the two GJW 14C dates were to be accurate, it would probably be the Harvard range (650–870 CE), which is corroborated by the related GJohn manuscript (chart above). Having said this, the result remains somewhat inconclusive. (δ13C levels were also higher than expected, suggesting contamination in all samples.)

So does this confirm the authenticity of the GJW? Such a late dating bulldozes King’s first appraisal of the manuscript as a fourth century witness. The GJW fragment under question is broken on all sides except the top, where apparently the modern forger cut the empty section off of a larger fragment which was in fact ancient. Carbon dating has no value for authenticating such a manuscript, although if the Ptolemaic date (410–200 BCE) offered by the Arizona AMS lab were accurate (of which I am not convinced), fraud would be certain.

PALEOGRAPHY

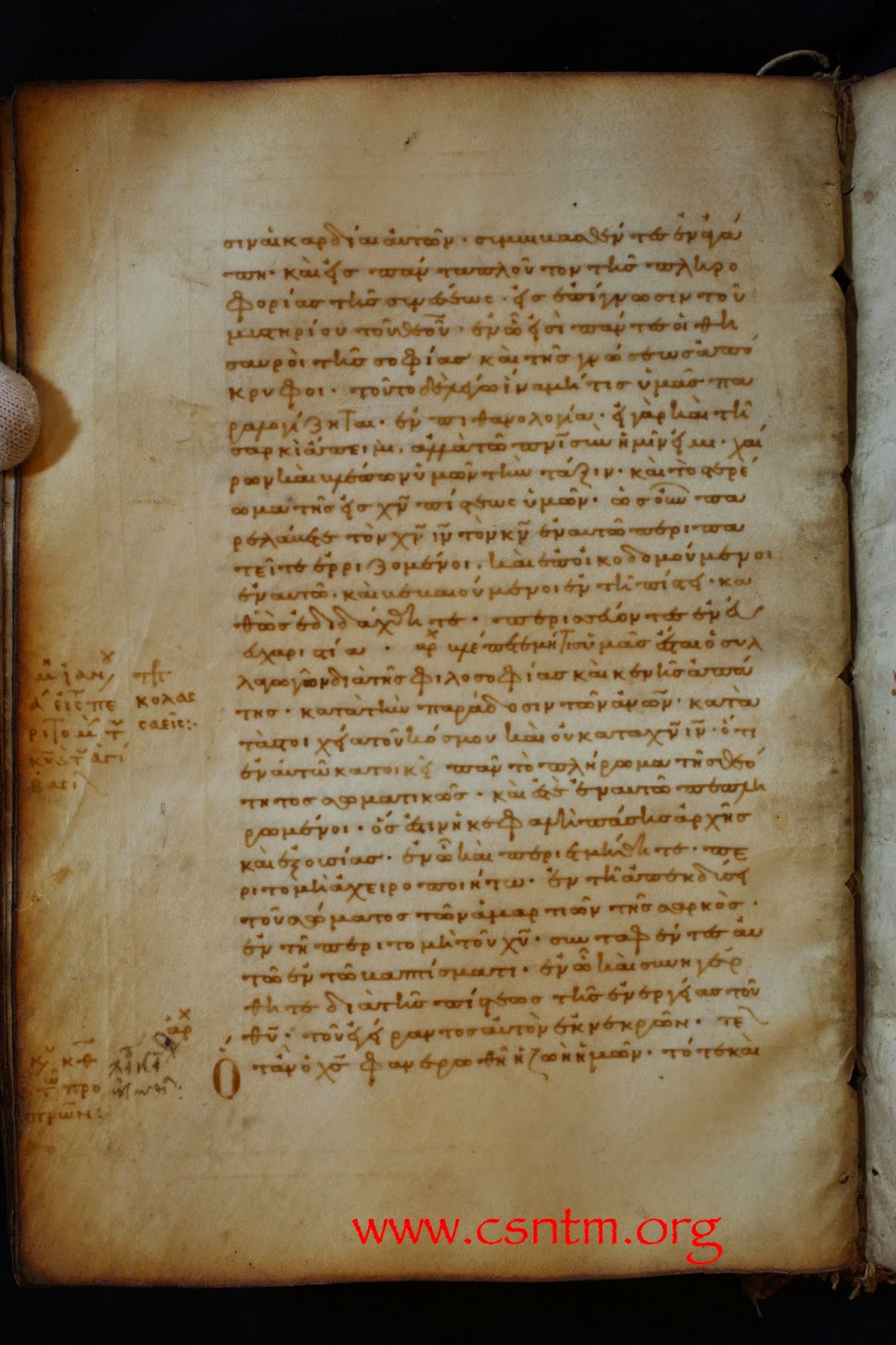

Choat’s assessment of the scribal hand is hardly an enthusiastic endorsement of its authenticity:

“Overall, if the general appearance of the papyrus prompts some suspicion, it is difficult to falsify by a strictly paleographical examination. This should not be taken as proof that the papyrus is genuine, simply that its handwriting and the manner in which it has been written do not provide definitive grounds for proving otherwise.” (162)His article surveys the oddities of the scribal hand, noting the lack of clear literary or documentary parallels. Choat states, “[w]hile I cannot adduce an exact parallel, I am inclined to compare paraliterary productions such as magical or educational texts.” (Choat, 161)

DEPUYDT

Leo Depuydt presents the argument which is accepted by most specialists who are familiar with the GJW. The modern forger (1) created the text by rearranging several sentences from the Gospel of Thomas and (2) unintentionally left evidence of the fraud through two grammatical infelicities ("blunders"). The first is the omission of the object marker ⲙ- in line one (ⲧⲁⲙⲁⲁⲩ ⲁⲥϯ ⲛⲁⲉⲓ ⲡⲱ̣[ⲛϩ]). The second is the awkward construction ⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ (more correctly ⲡⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ or ⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉϥⲑⲟⲟⲩ). Depuydt also mentioned a third serious error, which I believe to be the most damning evidence against authenticity (186); in line 6, the forger has combined a positive habitual from GThomas with a negative habitual to create the nonsense chimera verbal phrase ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲣⲱⲙⲉ ⲉⲑⲟⲟⲩ ϣⲁϥⲉ{ⲓ}ⲛⲉ (“Evil man habitually does not he does habitually bring” sic). Notably, Francis Watson, Alin Suciu-Hugo Lundhaug, and Andrew Bernhard have popularized many of these arguments, detailing how Depuydt’s first "blunder" seems to derive from a typo in Michael Grondin’s 2002 online PDF of the Gospel of Thomas.

KING’S RESPONSE ARTICLE

In Karen King’s mind, if one can not exhaustively prove the inauthenticity of the GJW fragment, then it must be accepted as authentic. The results from spectography, radiometric dating and Choat’s paleographic analysis all leave the door open, therefore the fragment is undeniably authentic. Karen King maintains the problematic infinitive form ϣⲁϥⲉ “swell,” and ignores the persuasive reasoning behind the reconstruction of the damning error above. I encountered no serious discussion of this in her original article. In my opinion, this argument alone inauthenticates the GJW fragment, yet King is unconcerned, instead positing an unattested verbal form. I could imagine why someone might differ with me on various issues here, I can not identify with the stiff-necked concluding statement of King: “In conclusion, Depuydt’s essay does not offer any substantial evidence or persuasive argument, let alone unequivocal surety, that the GJW fragment is a modern fabrication (forgery).”

CONCLUSION

If a husband were to genetically test his children to determine whether his wife had been faithful, and the tests returned indicating that the children could not conclusively be proven to not be his, would this assure him of his wife’s fidelity? Could he then, based upon these tests, be confident that he had indeed fathered the children? Karen King has produced no new evidence to authenticate this fragment. On the contrary, her prior contentions that the GJW fragment was (1) part of a literary codex and (2) was fourth century are now indefensible. Her method of argumentation was not self-critical or objective, but will doubtlessly be sufficient for those who already want to believe.

THE HANDWRITTEN NOTE

One has to ask why Karen King has not published the notorious handwritten note. A typed 1982 note signed by Peter Munro accompanied the fragments which indicated that a Coptic John fragment was among the manuscript group (cf. King, “Jesus said,” 2012, 2). The second notorious handwritten note reads as follows:

“Professor Fecht believes that the small fragment, approximately 8 cm in size, is the sole example of a text in which Jesus uses direct speech with reference to having a wife. Fecht is of the opinion that this could be evidence for a possible marriage.” (King, “Jesus said,” 2014, 153)Odd, is it not, that Munro mentioned a dime-a-dozen Sahidic manuscript in the typed note, but detailed the GJW in a handwritten note separately?! This handwritten note potentially bears the hand of the forger, who cut the papyrus, falsified the text, and aided its journey with the convenient handwritten note. King’s failure to publish this handwritten note conveniently eliminates a clear avenue for identifying the perpetrator.

Larry Hurtado's Announcement

Harvard Gospel of Jesus' Wife website

Harvard Theological Review Issue

Antinoou Coptic font to view Coptic text on this page

Francis Watson maintains inauthenticity (via NT Blog)

.jpg)