↧

Museum of the Bible Video

↧

Keith Elliott Festschrift

Textsand Traditions: Essays in Honour of J Keith Elliott (ed. J. Kloha & P. Doble; NTTSD 47; Leiden: Brill, 2014),

The methodology of New Testament textual criticism, the critical evaluation of readings, and the history and texts of early Christianity is the focus of the influential work of J. K. Elliott. Readings in Early Christianity: Texts and Traditions offers eighteen essays in his honour. The essays, by colleagues and students from his long career, reflect Elliott's wide interest and impact. From questions of the purpose and practice of textual criticism, to detailed assessment of New Testament literature and the readings of its manuscripts, to provocative studies of the reception of Jesus and the New Testament in the second century, this volume will be of value to those studying the New Testament and Early Christianity.

Table of contents

Michael W. Holmes, When Criteria Conflict

D. C. Parker, Variants and Variance

Eldon Jay Epp, In the Beginning Was the New Testament Text, But Which Text? A Consideration of ‘Ausgangstext’ and ‘Initial Text’*

Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, Eclecticism and the Book of Acts

James A. Kelhoffer, Hapless Disciples and Exemplary Minor Characters in the Gospel of Mark: The Exhortation to Cross-bearing as both Encouragement and Warning

James W. Voelz, The Characteristics of the Greek of St. Mark’s Gospel

Tjitze Baarda, The Syro-Sinaitic Palimpsest and Ephraem Syrus in Luke 2:36-38 and 1:6

Peter Doble, Codex Bezae and Luke 3:22: A Contribution to Discussion

Jeffrey Kloha, Elizabeth’s Magnificat (Luke 1:46)

H. A. G. Houghton, A Flock of Synonyms? John 21:15-17 in Greek and Latin Tradition

L. W. Hurtado, Textual Ambiguity and Textual Variants in Acts of the Apostles

Holger Strutwolf, Urtext oder frühe Korruption? Einige Beispiele aus der Apostelgeschichte

J. Lionel North, 1 Corinthians 8:6: From Confession to Paul to Creed to Paul

Peter M. Head, Tychicus and the Colossian Christians: A Reconsideration of the Text of Colossians 4:8

David R. Cartlidge, How to Draw an Immaculate Conception: Protevangelium of James 11-12 in Early Christian Art

Paul Foster, The Education of Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas

Denise Rouger et Christian-B. Amphoux, Le projet littéraire d’Ignace d’Antioche dans sa Lettre aux Ephésiens

William J. Elliott, How to Change a Continuous Text Manuscript into a Lectionary Text

Bibliography J. K. Elliott

D. C. Parker, Variants and Variance

Eldon Jay Epp, In the Beginning Was the New Testament Text, But Which Text? A Consideration of ‘Ausgangstext’ and ‘Initial Text’*

Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, Eclecticism and the Book of Acts

James A. Kelhoffer, Hapless Disciples and Exemplary Minor Characters in the Gospel of Mark: The Exhortation to Cross-bearing as both Encouragement and Warning

James W. Voelz, The Characteristics of the Greek of St. Mark’s Gospel

Tjitze Baarda, The Syro-Sinaitic Palimpsest and Ephraem Syrus in Luke 2:36-38 and 1:6

Peter Doble, Codex Bezae and Luke 3:22: A Contribution to Discussion

Jeffrey Kloha, Elizabeth’s Magnificat (Luke 1:46)

H. A. G. Houghton, A Flock of Synonyms? John 21:15-17 in Greek and Latin Tradition

L. W. Hurtado, Textual Ambiguity and Textual Variants in Acts of the Apostles

Holger Strutwolf, Urtext oder frühe Korruption? Einige Beispiele aus der Apostelgeschichte

J. Lionel North, 1 Corinthians 8:6: From Confession to Paul to Creed to Paul

Peter M. Head, Tychicus and the Colossian Christians: A Reconsideration of the Text of Colossians 4:8

David R. Cartlidge, How to Draw an Immaculate Conception: Protevangelium of James 11-12 in Early Christian Art

Paul Foster, The Education of Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas

Denise Rouger et Christian-B. Amphoux, Le projet littéraire d’Ignace d’Antioche dans sa Lettre aux Ephésiens

William J. Elliott, How to Change a Continuous Text Manuscript into a Lectionary Text

Bibliography J. K. Elliott

↧

↧

Early image of Christ holding a book

The BBC reports the find of a glass plate in Spain (here). It mentions a 4th century date for this artefact, which may be true or not. The reconstruction is interesting:

![]()

The central figure holding the cross is in all likelihood a depiction of Christ, while the two others I would take as the angels present at the resurrection, not unlike the Gospel of Peter. What is interesting though, is that Christ holds a small codex in his hand, while both companions each seem to hold a scroll.

The central figure holding the cross is in all likelihood a depiction of Christ, while the two others I would take as the angels present at the resurrection, not unlike the Gospel of Peter. What is interesting though, is that Christ holds a small codex in his hand, while both companions each seem to hold a scroll.

↧

Conference of the European Society for Textual Scholarship

TEXTUAL TRAILS. Transmissions of Oral and Written Texts

Helsinki, 30 October – 1 November 2014

Texts tend to travel across space and time, whether they are carried by sound waves, embedded in parchments, codices and books, or stored online. They pass from mouth to mouth, from singers' performances to scholars' notes, from stone engravings to printed books, or from writing desks to digital editions, and each of these transmissions leaves traces...The eleventh international conference of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, TEXTUAL TRAILS. Transmissions of Oral and Written Texts (Helsinki, 30 October – 1 November 2014), will explore all kinds of textual trails from various angles of scholarly editing and textual scholarship.

We are looking forward to an exciting three-day programme with almost 70 papers by textual scholars from four continents and over twenty countries.

Programme and registration:

↧

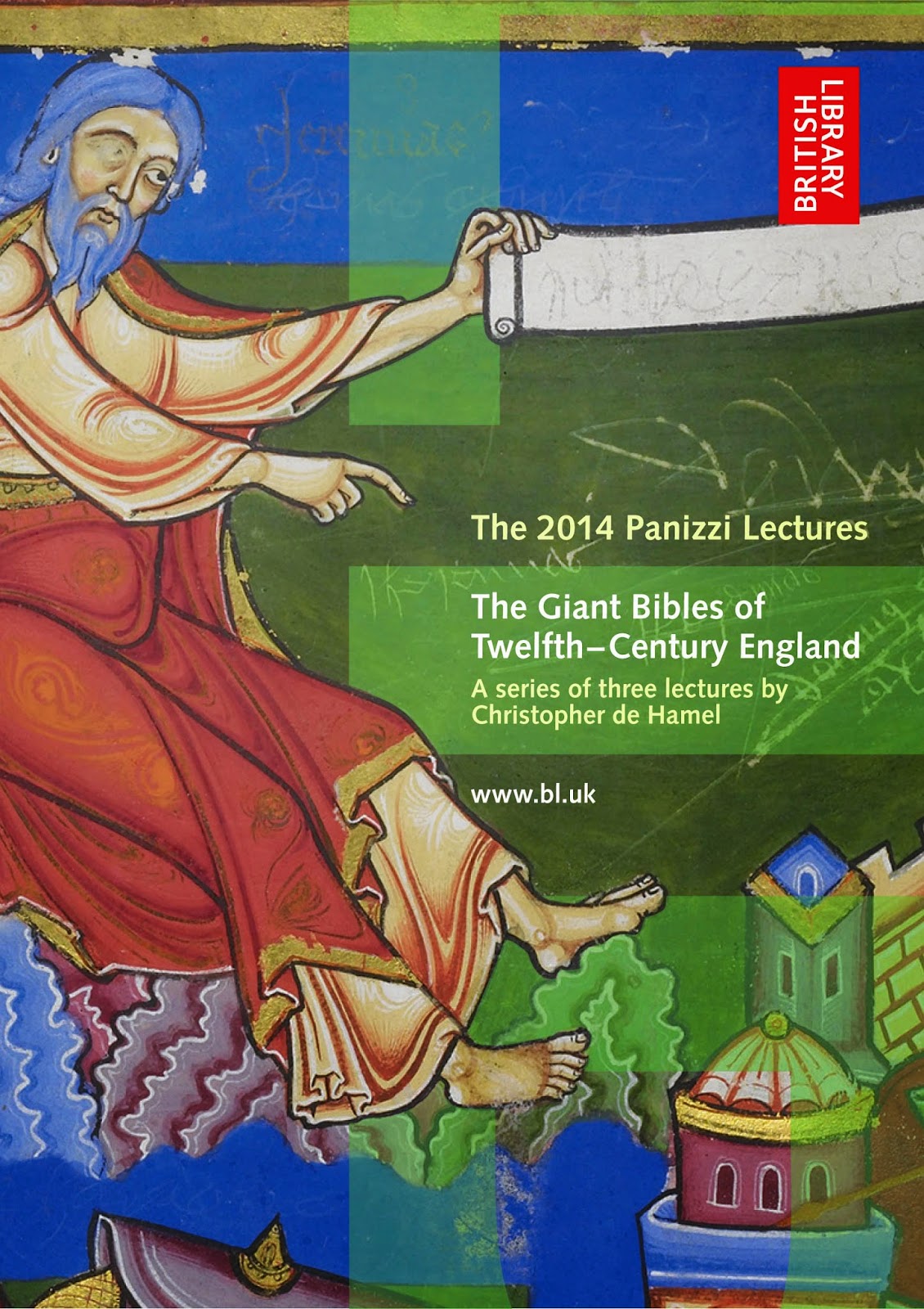

2014 Panizzi Lectures

The Giant Bibles of Twelfth-Century England

A series of three lectures in the British Library by Christopher de Hamel

The great Latin Bibles, in huge multiple volumes, are by far the largest and most spectacular manuscripts commissioned in England in the 12th century, decorated with magnificent illuminated pictures. The lectures will consider the purpose of such books and why they were suddenly so fashionable and also why they passed out of fashion in England during the second half of the 12th century.

1: The Bury Bible

Mon 27 Oct 2014, 18.15-19.30

The first lecture will consider the purpose of such books and why they were suddenly so fashionable. It will look principally at the Bible of Bury St Edmunds Abbey, now in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The manuscript was commissioned in the time of Anselm, abbot of Bury 1121-48. A chronicle of the abbey records that the cost for it was found by Hervey, brother of Talbot the prior, and that the manuscript was incomparably decorated by the hand of Master Hugo. The work is usually dated to around 1130. Hugo is the earliest professional artist in England whose name is known.

This lecture will discuss what we can tell about Hugo and his work, from close examination of the manuscript itself. It will look at the larger questions of where exemplars and materials were found for the Bible, and at the phenomenal expense of such undertakings.

2: The Winchester Bible

Thu 30 Oct 2014, 18.15-19.30

The Winchester Bible is still in the cathedral where it was commissioned, doubtless by Henry of Blois, bishop of Winchester 1129-71. It too was illuminated by professional painters, who apparently also worked on frescoes in Spain. This year the manuscript is being rebound in preparation for exhibition in New York and eventual installation in a new display gallery in Winchester Cathedral.

The lecture will take advantage of its disbinding to make new observations about its production, and to suggest new dates for the different phases of the work, undertaken in parallel with a second (but lesser) giant Bible from Winchester, now in the Bodleian Library, MS Auct. E. Infra 1 and 2. These two Bibles were constantly changed and upgraded during production, which came to an abrupt end on the death of Henry of Blois on 8 August 1171. They were then taken up again a decade later, the Bodleian Bible was finally completed, and the two sets were corrected against each other. The Winchester volumes, however, were eventually abandoned a second time and were wrapped up still unfinished.

3: The Lambeth Bible

Mon 3 Nov 2014, 18.15-19.30

One volume of the vast Lambeth Bible has been in the library of Lambeth Palace since its foundation in 1610. The long-lost second volume is owned by All Saints’ Church in Maidstone and is on permanent deposit at the Maidstone Museum. Despite its fame and quality of illumination, nothing has been hitherto known about the Bible’s original owner or patron.

This lecture will propose that it was commissioned around 1148 for Faversham Abbey by King Stephen, king of England 1135-54, elder brother of Henry of Blois and protagonist with the Empress Matilda in the civil war of the 12th century. This involves analysis of the unusual iconography of the miniatures, rich in dynastic imagery, and an investigation of the earlier career of the principal artist in the production of manuscripts in a professional scriptorium at Avesnes Abbey in Flanders.

A series of three lectures in the British Library by Christopher de Hamel

The great Latin Bibles, in huge multiple volumes, are by far the largest and most spectacular manuscripts commissioned in England in the 12th century, decorated with magnificent illuminated pictures. The lectures will consider the purpose of such books and why they were suddenly so fashionable and also why they passed out of fashion in England during the second half of the 12th century.

1: The Bury Bible

Mon 27 Oct 2014, 18.15-19.30

The first lecture will consider the purpose of such books and why they were suddenly so fashionable. It will look principally at the Bible of Bury St Edmunds Abbey, now in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The manuscript was commissioned in the time of Anselm, abbot of Bury 1121-48. A chronicle of the abbey records that the cost for it was found by Hervey, brother of Talbot the prior, and that the manuscript was incomparably decorated by the hand of Master Hugo. The work is usually dated to around 1130. Hugo is the earliest professional artist in England whose name is known.

This lecture will discuss what we can tell about Hugo and his work, from close examination of the manuscript itself. It will look at the larger questions of where exemplars and materials were found for the Bible, and at the phenomenal expense of such undertakings.

2: The Winchester Bible

Thu 30 Oct 2014, 18.15-19.30

The Winchester Bible is still in the cathedral where it was commissioned, doubtless by Henry of Blois, bishop of Winchester 1129-71. It too was illuminated by professional painters, who apparently also worked on frescoes in Spain. This year the manuscript is being rebound in preparation for exhibition in New York and eventual installation in a new display gallery in Winchester Cathedral.

The lecture will take advantage of its disbinding to make new observations about its production, and to suggest new dates for the different phases of the work, undertaken in parallel with a second (but lesser) giant Bible from Winchester, now in the Bodleian Library, MS Auct. E. Infra 1 and 2. These two Bibles were constantly changed and upgraded during production, which came to an abrupt end on the death of Henry of Blois on 8 August 1171. They were then taken up again a decade later, the Bodleian Bible was finally completed, and the two sets were corrected against each other. The Winchester volumes, however, were eventually abandoned a second time and were wrapped up still unfinished.

3: The Lambeth Bible

Mon 3 Nov 2014, 18.15-19.30

One volume of the vast Lambeth Bible has been in the library of Lambeth Palace since its foundation in 1610. The long-lost second volume is owned by All Saints’ Church in Maidstone and is on permanent deposit at the Maidstone Museum. Despite its fame and quality of illumination, nothing has been hitherto known about the Bible’s original owner or patron.

This lecture will propose that it was commissioned around 1148 for Faversham Abbey by King Stephen, king of England 1135-54, elder brother of Henry of Blois and protagonist with the Empress Matilda in the civil war of the 12th century. This involves analysis of the unusual iconography of the miniatures, rich in dynastic imagery, and an investigation of the earlier career of the principal artist in the production of manuscripts in a professional scriptorium at Avesnes Abbey in Flanders.

↧

↧

Nongbri on the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri (Michigan Portion)

In the recent issue of Archiv für Papyrusforschung 60/1 (2014), Brent Nongbri has published an article on "The Acquisition of the University of Michigan's Portion of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri and a New Suggested Provenance."

In the recent issue of Archiv für Papyrusforschung 60/1 (2014), Brent Nongbri has published an article on "The Acquisition of the University of Michigan's Portion of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri and a New Suggested Provenance."The title perhaps sounds too optimistic in regard to provenance—to cite the conclusion:

The goal of this paper was two-fold – to clarify the history of acquisitions of Beatty biblical papyri and to reassess what we know of the provenance of the find. I am reasonably satisfied with the results of the first task. As to the reassessment of provenance, I think dissatisfaction is the order of the day.Brent has kindly made his article available here.

↧

Mozart Manuscript discovered ... in a library!

A young researcher, named Balazs Mikusi, found Mozart's own score of the Piano Sonata in A. He was a clever researcher because he was in a library 'leafing through folders of unidentified manuscripts'. That is the best place to discover manuscripts.

He said in an interview: 'I think it is reassuring to know that we are getting closer to what Mozart really meant when he composed this piece.'

He said in an interview: 'I think it is reassuring to know that we are getting closer to what Mozart really meant when he composed this piece.'

↧

Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New Testament on Sale!

Gorgias Press has a sale until 31 December on this newly published volume of ten papers presented at the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament:

Gorgias Press has a sale until 31 December on this newly published volume of ten papers presented at the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament: Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New TestamentEdited by H. A. G. Houghton

(Texts and Studies 11)

ISBN:978-1-4632-0411-2

Sale price: $57.00 (50%)

Contributions by Thomas O'Loughlin, Hans Förster, Ulrike Swoboda, Satoshi Toda, Rebekka Schirner, Oliver Norris, Rosalind MacLachlan, Matthew Steinfeld, Amy Anderson and Simon Crisp.

The New Testament text has a long and varied history, in which readers, scholars and editors all play a part. Understanding the ways in which these users engage with the text, including the physical form in which they encounter the Bible, its role in liturgy, the creation of scholarly apparatus and commentary, types of quotation and allusion, and creative rewriting in different languages or genres, offers insight into its tradition and dissemination.Table of Contents

The ten papers in this volume present original research focusing on primary material in a variety of fields and languages. Their scope stretches from the evidence in the gospels for ‘ministers of the word’, and the sources used by the evangelists, to the complex history and politics of a twentieth-century critical edition. Key third- and fourth-century figures are assessed, including Origen, Eusebius of Caesarea and Augustine, as well as an anonymous commentary on Paul used by Pelagius and only preserved in a single ninth-century manuscript. Traces of a pre-Vulgate Latin version are detected in the poetry of Sedulius, while early translations in general are explored as a way of shedding light on the initial reception of the gospels. One of the earliest scholarly ‘editions’ of the gospels, underlying the manuscripts known as Family 1, is examined in Mark.

The contributors were all participants in the eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, an international gathering of established and emerging scholars whose work reflects the excitement and diversity of New Testament textual scholarship today.

• Table of Contents (page 7)

• List of Contributors (page 9)

• Introduction (page 11)

• List of Abbreviations (page 15)

• 1. Hupêretai ... tou logou: Does Luke 1:2 Throw Light on to the Book Practices of the Late First-Century Churches? (Thomas O'Loughlin) (page 17)

• 2. The Gospel of John and its Original Readers (Hans Forster in co-operation with Ulrike Swoboda) (page 33)

• 3. The Eusebian Canons: Their Implications and Potential (Satoshi Toda) (page 43)

• 4. Donkeys or Shoulders? Augustine as a Textual Critic of the Old and New Testaments (Rebekka Schirner) (page 61)

• 5. The Sources for the Temptations Episode in the Paschale Carmen of Sedulius (Oliver Norris) (page 83)

• 6. A Reintroduction to the Budapest Anonymous Commentary on the Pauline Letters (R. F. MacLachlan) (page 109)

• 7. Preliminary Investigations of Origen's Text of Galatians (Matthew R. Steinfeld) (page 123)

• 8. Family 1 in Mark: Preliminary Results (Amy S. Anderson) (page 135)

• 9. Textual Criticism and the Interpretation of Texts: The Example of the Gospel of John (Hans Forster) (page 179)

• 10. The Correspondence of Erwin Nestle with the BFBS and the 'Nestle-Kilpatrick' Greek New Testament Edition of 1958 (Simon Crisp) (page 205)

• Index of Manuscripts (page 223)

• Index of Biblical Passages (page 225)

• Index of Subjects (page 229)

• Index of Greek Words (page 233)

Order here.

↧

A Survey of Surveys on Mark

Here is a collection of surveys of scholarship on Mark. I couldn't find one which summarised text-critical work on Mark's Gospel.

Surveys of Scholarly Literature:

R.S. Barbour, ‘Recent Study of the Gospel according to St. Mark’ Exp T 79 (1967-68), 324-329.

H.C. Kee, ‘Mark as Redactor and Theologian: A Survey of some recent Markan Studies’ JBL 90 (1971), 333-336.

H.C. Kee, ‘Mark’s Gospel in Recent Resarch’ Interpretation 32 (1978), 353-368.

S.P. Kealy, Mark’s Gospel: A History of its Interpretation, From the Beginning Until 1979 (New York: Paulist, 1982).

D.J. Harrington, ‘A Map of Books on Mark (1975-1984)’ BTB 15 (1985), 12-16

W. Telford, ‘Introduction: The Gospel of Mark’ The Interpretation of Mark (ed. W. Telford; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1985), 1-41.

L.W. Hurtado, ‘The Gospel of Mark in recent study’ Themelios 14 (1989), 47-52.

W.L. Lane, ‘The Present State of Markan Studies’ The Gospels Today: A Guide to Some Recent Developments (The New Testament Student VI; ed. J.H. Skilton, M.J. Robertson III & W.L. Lane; Philadelphia: Skilton House, 1990), 51-81.

F.J. Matera, What are they Saying about Mark? (New York: Paulist, 1987).

M.M. Jacobs, ‘Mark’s Jesus through the Eyes of Twentieth Century New Testament Scholars’ Neotestamentica 28 (1994), 53-85.

W. Telford, ‘The Interpretation of Mark: A History of Developments and Issues’ The Interpretation of Mark (ed. W. Telford; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1995, 2nded.), 1-61.

P.G. Bolt, ‘Mark’s Gospel’ in The Face of New Testament Studies: A Survey of Recent Research (ed. S. McKnight & G.R. Osborne; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004), 391-413.

K.W. Larsen, ‘The Structure of Mark’s Gospel: Current Proposals’ CBR 3 (2004), 140-160.

D.J. Harrington, What are they Saying about Mark? (New York: Paulist, 2004).

W. Telford, Writing on the Gospel of Mark (Guides to Advanced Biblical Research 1; Blandford Forum: Deo, 2009)

C. Breytenbach, ‘Current Research on the Gospel according to Mark: A Report on Monographs Published from 2000-2009’ in Mark and Matthew I: Comparative Readings: Understanding the Earliest Gospels in their First-Century Settings (ed. E-M. Becker & A. Runesson; WUNT I.271; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011), 13-32.

H. M. Humphrey, A Bibliography for the Gospel of Mark, 1954-1980 (Studies in the Bible and Early Christianity, 1; New York: Edwin Mellen, 1981).

H.M. Humphrey, The Gospel of Mark: An Indexed Bibliography 1980-2005 (New York: Edwin Mellen, 2006).

F. Neirynck (et al.), The Gospel of Mark: A Cumulative Bibliography, 1950-1990 (BETL 102; Leuven: Leuven UP & Peeters, 1992).

↧

↧

British Library, Matthew 23 and Chrysostom

Though I don't think that there is much biblical stuff in the latest batch of Greek mss put online by the British Library, there is always something interesting, and this time it is a citation from the Gospel of Matthew. You can find the BL blog post here from which I copied below the image of Add MS 24371, sermons by Chrysostom.

![]()

At the top of the page Mat 23:1-3 is cited and these words are marked, as usual, with diples '>>' in the left margin.

There is a nice textual variant here from line 6 on: πάντα οὖν ὅσα ἄν λέγωσιν ὑμῶν ποιεῖν, ποιεῖτε. (All that they tell you to do, do).

The words ποιειν ποιειτε 'to do, do' are rather rare, I found only two manuscripts in Legg's Matthew volume that have these words, Γ(036) (here) and minuscule 544 (here). Now if I had time I'd love to pursue this and trace the relation between Γ(036), 544 and Chrysostom's text further, but alas ...

At the top of the page Mat 23:1-3 is cited and these words are marked, as usual, with diples '>>' in the left margin.

There is a nice textual variant here from line 6 on: πάντα οὖν ὅσα ἄν λέγωσιν ὑμῶν ποιεῖν, ποιεῖτε. (All that they tell you to do, do).

The words ποιειν ποιειτε 'to do, do' are rather rare, I found only two manuscripts in Legg's Matthew volume that have these words, Γ(036) (here) and minuscule 544 (here). Now if I had time I'd love to pursue this and trace the relation between Γ(036), 544 and Chrysostom's text further, but alas ...

↧

Call for Papers: Jeremiah, Scripture and Theology

The Fifth St Andrews Scripture and Theology Conference: The Book of Jeremiah, 6-9 July 2015

In July 2015, biblical scholars and theologians from around the world will gather to consider the Book of Jeremiah, using this ancient text to bring exegesis and theology into conversation. The conference organisers and the School of Divinity at the University of St Andrews are delighted to invite you to join the conversation.You can also find us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/2015Jeremiah and follow us on Twitter at https://twitter.com/2015Jeremiah (@2015Jeremiah).Further details of registration will appear here in early Autumn; in the meantime, please submit paper proposals of no more than 500 words (not including paper titles) to Penelope Barter pb242@st-andrews.ac.uk. Proposals are due by midnight GMT on Friday 27th Feburary 2015 for consideration in early March.

↧

SBL ETC Blog Dinner

When:

Sunday, 23 Nov 23, 7pm

Where:

The Hard Rock Cafe

Group Menu Price:

$22

For those of you attending SBL and interested in textual criticism, the annual blog dinner will take place after the NTTC session on Sunday night "Nestle-Aland 28th Revised Edition" (4:00-6:30pm, Hilton Bayfront, Sapphire Ballroom L). After the session finishes, we will walk together to the Hard Rock, where we have reserved the "Surf Shack" room. The $22 group menu choice is required for the room reservation, and includes a beverage, entrée, dessert, tax and gratuity. If you wish to join us, please RSVP in the comments below or send me an email. The invitation is open to all who are interested in textual criticism, and who are desirous to hear Peter Head's customary year-in-review speech.

Sunday, 23 Nov 23, 7pm

Where:

The Hard Rock Cafe

Group Menu Price:

$22

For those of you attending SBL and interested in textual criticism, the annual blog dinner will take place after the NTTC session on Sunday night "Nestle-Aland 28th Revised Edition" (4:00-6:30pm, Hilton Bayfront, Sapphire Ballroom L). After the session finishes, we will walk together to the Hard Rock, where we have reserved the "Surf Shack" room. The $22 group menu choice is required for the room reservation, and includes a beverage, entrée, dessert, tax and gratuity. If you wish to join us, please RSVP in the comments below or send me an email. The invitation is open to all who are interested in textual criticism, and who are desirous to hear Peter Head's customary year-in-review speech.

↧

Oxford Syriac Conference Jan 2015: Call for Papers

Syriac Intellectual Culture in Late Antiquity

Translation, transmission, and influence

The conference welcomes proposals for papers on the following and related topics:

- The reception and revision of Syriac biblical translations, especially works such as the Harklean and Syrohexaplaric versions and Jacob of Edessa’s Old Testament revision. How did Syriac authors navigate the diversity of translation options available to them? How were later translations and revisions received in both exegetical and liturgical contexts? Which textual variants were employed by exegetes, and in what contexts?

- What role do translations of Greek patristic literature, such as the works of Gregory Nazianzen and Theodore of Mopsuestia, play in the context of Syriac literature? How is material from Greek historiography, such as the ecclesiastical histories of Eusebius, Socrates, and Theodoret, translated and transmitted by Syriac chroniclers?

- What factors played a part in the development of literary canons and exegetical traditions in Syriac? How did different communities determine which texts to elevate to canonical status? When and why were authors from rival communities read and utilized? How did Greek-language authors, such as Severus of Antioch, undergo a process of ‘Syriacization’? Which authors survived the decline of spoken Syriac and were translated into Christian Arabic, and how?

- What forms did Syriac intellectual life take over the course of the period, in monastic, scholarly, and church communities? How did Syriac culture react to and interact with influences such as Aristotelian and neo-Platonist thought, rabbinic scholarship, and other vernacular literatures? What role did Syriac scholars play in the early development of Arabic-language intellectual culture, and how did this role affect or change their own traditions?

Those wishing to present a twenty-minute paper may submit a brief abstract (250 words or less) and academic biography to oxfordsyriac2015@gmail.com. The deadline for submissions is Monday, 17 November 2014.

↧

↧

Sahidic OT Project at Göttingen!!!

|

| Sahidic Job, Naples, National Library, Ms.I.B.18 |

↧

Your Greek New Testament and Revisions of Editions

There is something interesting going on in the apparatus of NA28. But I need a long introduction ...

For any critical edition of the Greek New Testament a decision is made which manuscript to include in the apparatus and which not. Nestle-Aland 28 divides the manuscripts up between ‘consistently cited manuscripts’ and the others. In the introduction to NA28 a clear (!) explanation is given why manuscripts were included as 'consistently cited'. Eighteen manuscripts were included because they have the ‘initial text’ as their closest potential ancestor. There is also a 19th manuscript in this category, minuscule 468, but this one was replaced with minuscule 307 since the Byzantine text was well represented anyway. In addition to these, 88 and 1881 are added for one of the letters only, 33 because it is so interesting, 1448 and 1611 because they are Harkleian, and 642 because it represents a particular Byzantine group. All the papyri are included as well. We all know that for the Catholic Epistles NA28 is dependent on the Editio Critica Maior, 2nd edition (ECM2) and there the continuous witnesses of the first sub-group above (the 18 + 1) are given under the label ‘witnesses that have A as potential ancestor with rank one’.

The term ‘closest potential ancestor’ comes from the Coherence Based Genealogical Method (and if you don’t understand what that is, you should come to the SBL session, which will teach you everything you need to know). What is important for now is that the CBGM is an iterative method, which shapes the overall structure of the witnesses according to the decisions you take during the editing process.

You can of course revisit again and again, but at some points you have to publish something. So the INTF published the Catholic Epistles between 1999 and 2005 (Editio Critica Maior, 1st edition), and the shape of the witness tradition at that particular point was reflected in version one of ‘Genealogical Queries’ (the database of decisions and data underlying the text). Lucky for them, the INTF had the opportunity to use the data collected at that particular point to go over the text of the Catholic Epistles again. So the starting point was ‘Genealogical Queries version one’, which developed in the course of editing the second edition of the Editio Critica Maior into ‘Genealogical Queries version two’.

At the start of working on ECM2, there was a list of witnesses that, at that point, had the initial text as their closest potential ancestor. It is this particular list that is given in the introduction to ECM2 as the witnesses with rank one. However, as a result of editing ECM2, this list changed quite a bit. In Genealogical Queries version two’, which reflects the decisions made for ECM2, three of the witnesses no longer have the initial text (A) as their closest ancestor, 442, 2344, and 2492. Now minuscule 442 has rank 8, 2344 rank 2, and 2492 has sunk all the way down to rank 11.

What does this mean for the justification of what manuscripts to include as ‘consistently cited witnesses’? The group of important manuscripts as found in the apparatus of NA28 is based on the group the editors started out with when working on the text, but is not the group of witnesses that they ended up with. Three of the manuscripts, at least within the method, appeared less important for the text that was produced then initially thought. If the selection of manuscripts to include in the apparatus was made again today, these three manuscripts might well be deselected (unless they were deemed to be interesting for some other reason).

So when do you use ‘Genealogical Queries version one’ and when ‘version two’? If you want to know what the editors started out with for the second edition, you use ‘one’, if you want to know what they ended up with, you use ‘two’. ‘Version two’ reflects the situation at the end of the process. But, counterintuitively, the data from ‘version one’ and not ‘version two’ have been used to draw up the list of ‘witnesses of rank one’ (in ECM2 terminology) which is the same as the first group of ‘consistently cited witnesses’ (NA28 terminology). Current thinking would have left out the three witnesses mentioned earlier.

I needed some patient help from Klaus Wachtel to explain the background and that the pressure of publishing was a big factor in setting up ‘Genealogical Queries version 2’ only after NA28 and ECM2 went to press. And I needed Peter Gurry to point out to me that the list in ECM2 had something to do with the consistently cited witnesses for the Catholic Epistles in NA28. I just hope I have explained all the confusion correctly.

So what was the interesting thing going on in the apparatus of NA28? Well, three of the manuscripts cited in the Catholic Epistles (442, 2344, and 2492) do not have an obvious right to be there.

We don’t make it ourselves easy in this discipline, do we?

For any critical edition of the Greek New Testament a decision is made which manuscript to include in the apparatus and which not. Nestle-Aland 28 divides the manuscripts up between ‘consistently cited manuscripts’ and the others. In the introduction to NA28 a clear (!) explanation is given why manuscripts were included as 'consistently cited'. Eighteen manuscripts were included because they have the ‘initial text’ as their closest potential ancestor. There is also a 19th manuscript in this category, minuscule 468, but this one was replaced with minuscule 307 since the Byzantine text was well represented anyway. In addition to these, 88 and 1881 are added for one of the letters only, 33 because it is so interesting, 1448 and 1611 because they are Harkleian, and 642 because it represents a particular Byzantine group. All the papyri are included as well. We all know that for the Catholic Epistles NA28 is dependent on the Editio Critica Maior, 2nd edition (ECM2) and there the continuous witnesses of the first sub-group above (the 18 + 1) are given under the label ‘witnesses that have A as potential ancestor with rank one’.

The term ‘closest potential ancestor’ comes from the Coherence Based Genealogical Method (and if you don’t understand what that is, you should come to the SBL session, which will teach you everything you need to know). What is important for now is that the CBGM is an iterative method, which shapes the overall structure of the witnesses according to the decisions you take during the editing process.

You can of course revisit again and again, but at some points you have to publish something. So the INTF published the Catholic Epistles between 1999 and 2005 (Editio Critica Maior, 1st edition), and the shape of the witness tradition at that particular point was reflected in version one of ‘Genealogical Queries’ (the database of decisions and data underlying the text). Lucky for them, the INTF had the opportunity to use the data collected at that particular point to go over the text of the Catholic Epistles again. So the starting point was ‘Genealogical Queries version one’, which developed in the course of editing the second edition of the Editio Critica Maior into ‘Genealogical Queries version two’.

At the start of working on ECM2, there was a list of witnesses that, at that point, had the initial text as their closest potential ancestor. It is this particular list that is given in the introduction to ECM2 as the witnesses with rank one. However, as a result of editing ECM2, this list changed quite a bit. In Genealogical Queries version two’, which reflects the decisions made for ECM2, three of the witnesses no longer have the initial text (A) as their closest ancestor, 442, 2344, and 2492. Now minuscule 442 has rank 8, 2344 rank 2, and 2492 has sunk all the way down to rank 11.

What does this mean for the justification of what manuscripts to include as ‘consistently cited witnesses’? The group of important manuscripts as found in the apparatus of NA28 is based on the group the editors started out with when working on the text, but is not the group of witnesses that they ended up with. Three of the manuscripts, at least within the method, appeared less important for the text that was produced then initially thought. If the selection of manuscripts to include in the apparatus was made again today, these three manuscripts might well be deselected (unless they were deemed to be interesting for some other reason).

So when do you use ‘Genealogical Queries version one’ and when ‘version two’? If you want to know what the editors started out with for the second edition, you use ‘one’, if you want to know what they ended up with, you use ‘two’. ‘Version two’ reflects the situation at the end of the process. But, counterintuitively, the data from ‘version one’ and not ‘version two’ have been used to draw up the list of ‘witnesses of rank one’ (in ECM2 terminology) which is the same as the first group of ‘consistently cited witnesses’ (NA28 terminology). Current thinking would have left out the three witnesses mentioned earlier.

I needed some patient help from Klaus Wachtel to explain the background and that the pressure of publishing was a big factor in setting up ‘Genealogical Queries version 2’ only after NA28 and ECM2 went to press. And I needed Peter Gurry to point out to me that the list in ECM2 had something to do with the consistently cited witnesses for the Catholic Epistles in NA28. I just hope I have explained all the confusion correctly.

So what was the interesting thing going on in the apparatus of NA28? Well, three of the manuscripts cited in the Catholic Epistles (442, 2344, and 2492) do not have an obvious right to be there.

We don’t make it ourselves easy in this discipline, do we?

↧

Conference on the Bodmer Papyri (Feb 2014)

Further details (including abstracts of papers) from Alin Suciu's blog

↧

Green Scholars Initiative, new director announced

The Museum of the Bible has announced that ETC blog member, Michael Holmes, has been chosen to lead the Green Scholars Initiative. You can read the full announcement, here. The following excerpt details Mike's placement:

Assuming the role of executive director of the Green Scholars Initiative, Holmes will lead a team of researchers and student-scholars at more than 60 universities around the world advancing groundbreaking discoveries on artifacts from the Green Collection. Holmes holds a doctorate from Princeton Theological Seminary, where he also taught New Testament, and continues in his role as University Professor of Biblical Studies and Early Christianity at Bethel University. He is a frequent speaker and international lecturer who has authored 11 books on biblical and early Christian writings.Further information on Michael Holmes may be found on his university webpage, here. Congratulations, Mike, from all of us on the blog!

↧

↧

Ancient Textual Scholarship: Pseudo Aelius Herodianus

The Partitiones contains orthographical and inflectional observations on Greek. A number of these words appear to come from the Greek Bible, both Old and New Testament, though the work in itself does not betray any ecclesiastical Christian connection. Under the initial syllable /i/, for example, the entry ιησους is glossed rather simplistically, as ο θεος. The work is ascribed to Aelius Herodianus (II AD), but apparently falsely so, according to the Neue Pauly. The Pinakes website lists his work under Herodianus Alexandrinus (also II AD), but I haven't seen any justification for this. A date of this work with its New Testament terms somewhere in the second century AD would be nice, but it is inherently unlikely that the writings of the New Testament (including Mark - Boanerges is mentioned) already had drawn attention from any grammarian. My own rule of thumb for dating anything is that if I don't have a clue it is likely to be fourth of fifth century AD.

Secondary literature on authorship, date or nature of the work seems absent (or at least I haven't found it; any help appreciated).

The Partitiones are potentially interesting because of some of the glosses and particular spellings, though these may have been influenced by liturgical influences or Byzantine linguistic updating. The explanation for Moses, μωσης is that it derives from μως (88.6), an explanation that would not work with the spelling μωυσης:

μῶς, τὸ ὕδωρ, ὅθεν καὶ Μωσῆς, κύριον.

There is clearly a relation with what Micheal Psellus (XI AD) writes:

53, 255-256

παρ'Αἰγυπτίοις γὰρ τὸ ‘μῶς’ ὕδωρ ἐστὶ σημαῖνον,

ὁ δὲ ληφθεὶς ἐξ ὕδατος Μωσῆς αὐτοῖς καλεῖται.

And possibly also with this passage from Joannes Zonaras (XII AD):

1.41.26-1.42.1

ἡ δέ “κάλεσον” ἔφη. καὶ παρήγαγε τὴν μητέρα, καὶ ἡ Θέρμουθις τὴν τοῦ παιδὸς τροφὴν ἔμμισθον αὐτῇ ἀνατίθησι, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ συμβεβηκότος ὀνομάζει αὐτό. τὸ γὰρ ὕδωρ μῶς καλοῦσιν Αἰγύπτιοι, ὑσῆς δὲ τοὺς σωθέντας ἐξ ὕδατος· ἄμφω γοῦν συνθεῖσα τὰ ῥήματα εἰς κλῆσιν αὐτοῖς τοῦ βρέφους ἐχρήσατο.

See also the spelling of Bethphage (accentuation as in TLG):

5.15

Πᾶσα λέξις ἀπὸ τῆς βη συλλαβῆς ἀρχομένη διὰ τοῦ η γράφεται· οἷον· Βηθλεὲμ, καὶ Βηθανία, Βηθεσδὰ, Βηθσαϊδὰ, καὶ Βηθσφαγὴ, ὀνόματα τόπων ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις·

The spelling Bethsphage is interesting and common in the later manuscript tradition. But is this an adaption, is there variation within the tradition of the Partitiones, or what? It seems that without a critical edition of the Partitiones and a good study on the contents there is little we can do as yet.

Secondary literature on authorship, date or nature of the work seems absent (or at least I haven't found it; any help appreciated).

The Partitiones are potentially interesting because of some of the glosses and particular spellings, though these may have been influenced by liturgical influences or Byzantine linguistic updating. The explanation for Moses, μωσης is that it derives from μως (88.6), an explanation that would not work with the spelling μωυσης:

μῶς, τὸ ὕδωρ, ὅθεν καὶ Μωσῆς, κύριον.

There is clearly a relation with what Micheal Psellus (XI AD) writes:

53, 255-256

παρ'Αἰγυπτίοις γὰρ τὸ ‘μῶς’ ὕδωρ ἐστὶ σημαῖνον,

ὁ δὲ ληφθεὶς ἐξ ὕδατος Μωσῆς αὐτοῖς καλεῖται.

And possibly also with this passage from Joannes Zonaras (XII AD):

1.41.26-1.42.1

ἡ δέ “κάλεσον” ἔφη. καὶ παρήγαγε τὴν μητέρα, καὶ ἡ Θέρμουθις τὴν τοῦ παιδὸς τροφὴν ἔμμισθον αὐτῇ ἀνατίθησι, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ συμβεβηκότος ὀνομάζει αὐτό. τὸ γὰρ ὕδωρ μῶς καλοῦσιν Αἰγύπτιοι, ὑσῆς δὲ τοὺς σωθέντας ἐξ ὕδατος· ἄμφω γοῦν συνθεῖσα τὰ ῥήματα εἰς κλῆσιν αὐτοῖς τοῦ βρέφους ἐχρήσατο.

See also the spelling of Bethphage (accentuation as in TLG):

5.15

Πᾶσα λέξις ἀπὸ τῆς βη συλλαβῆς ἀρχομένη διὰ τοῦ η γράφεται· οἷον· Βηθλεὲμ, καὶ Βηθανία, Βηθεσδὰ, Βηθσαϊδὰ, καὶ Βηθσφαγὴ, ὀνόματα τόπων ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις·

The spelling Bethsphage is interesting and common in the later manuscript tradition. But is this an adaption, is there variation within the tradition of the Partitiones, or what? It seems that without a critical edition of the Partitiones and a good study on the contents there is little we can do as yet.

↧

Codex Climaci Rescriptus contains Aratus and Eratosthenes

We've partially cracked the previously undeciphered 20 sides of Codex Climaci Rescriptus. They contain astronomical texts by Aratus and Eratosthenes. In the case of the latter this is the earliest known manuscript.

See further DeMoss press release.

See further DeMoss press release.

↧

Bible Odyssey Featuring "Alexandrian Text" and "Early Versions"

A year ago or so I was invited to contribute to SBL's project Bible Odyssey which was launched about two months ago. I was told that this week my article on the "Alexandrian Text" is highlighted on the Bible Oddysey home page, together with an article on "The Earliest Versions and Translations of the Bible" by Brennan Breed and a timeline of "The History of the English Bible" and a newly added videoclip on Early Christian Martyrdom featuring Candida Moss.

Just a week ago, John Kutsko of the SBL sent out a report about the two first months of the website, and it turns out that "People are very interested in ... 'life in first century Galilee' and 'how the Hebrew Bible relates to the ancient Near East,' as well as 'the binding of Isaac' and 'the woman caught in adultery.'” The last entry is written by my friend Jennifer Knust and we have worked a lot together on this topic for some years now. There is a related video clip in which Amy Jill Levine discusses the pericope adulterae, and another entry on the manuscript history of the passage (John 8:1-11) by another friend of mine, Chris Keith. Earlier this year, Chris, Jennifer and I contributed to a conference at SEBTS, the Pericope Adulterae symposium.

Kutsko continues his report on the Bible Odyssey webpage saying that many visitors come from North America and Europe, but that there is also strong traffic from Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Israel. Personally, Kutsko thinks the "Ask the Scholar" button (see the magnifying glass on the image above, or go here) is the coolest of all. Here they have received questions such as:

Just a week ago, John Kutsko of the SBL sent out a report about the two first months of the website, and it turns out that "People are very interested in ... 'life in first century Galilee' and 'how the Hebrew Bible relates to the ancient Near East,' as well as 'the binding of Isaac' and 'the woman caught in adultery.'” The last entry is written by my friend Jennifer Knust and we have worked a lot together on this topic for some years now. There is a related video clip in which Amy Jill Levine discusses the pericope adulterae, and another entry on the manuscript history of the passage (John 8:1-11) by another friend of mine, Chris Keith. Earlier this year, Chris, Jennifer and I contributed to a conference at SEBTS, the Pericope Adulterae symposium.

Kutsko continues his report on the Bible Odyssey webpage saying that many visitors come from North America and Europe, but that there is also strong traffic from Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Israel. Personally, Kutsko thinks the "Ask the Scholar" button (see the magnifying glass on the image above, or go here) is the coolest of all. Here they have received questions such as:

- Why does God speak in the plural in Genesis?

- Was John the Baptist an Essene?

- How many scholars believe that Q existed as a source for Matthew and Luke?

- Has the biblical figure of Satan evolved?

- Why is ‘almah in Proverbs 30:19 translated differently?

- How does domestic architecture vary in the Second Temple period?

↧